Guest post by member, Charles Bultman. He is an architect in Ann Arbor, Michigan who has been saving and adapting old, unwanted, barns into new uses; including homes, offices and retail spaces.

The scene is easily conjured; a barn in a field, quietly marking time. It’s a picture that lingers. Few things are as simple as an old barn. But that simplicity evaporates when we consider their future?

There are about 660,000 historic barns left in the United States. And while that may sound like a lot, at the peak of farming in America, around 1910, there were 6 million farms. If each farm had only one barn we have lost on average 50,000 barns a year. But obviously their demise does not come about ‘on average’. As the years pass more and more barns fall into ruin; making 660,000 seem like a frighteningly small number to me.

So what is to become of relics like barns when the country has been steadily moving to a non-agrarian lifestyle, and shows no real sign of turning back? These icons in the landscape are stranded but they are not without love. That’s why it is not so simple.

Barns in our landscape are sublime. Like a mountain or a river, they have existed there for so long that you can come to believe they will be there forever. But they will not. We have all heard the reasons; too much to maintain, farm equipment is too big, fewer farms and fewer farmers, etc. etc. etc.

But didn’t we agree that barns are loved? Why does that not swing in their favor?

With few exceptions old wood barns are destined to one of three possible futures. The first is that the barn is maintained, or restored, to be a barn. This is the most obvious requiring simply that the foundation be kept in good repair, the roof be replaced in a timely manner, and the frame and siding are kept dry and secure. But of course this costs money and most people do not spend this kind of money unless they need to. Without a farm these costs are difficult to justify, which is why the second future is the one we see the most; do little or nothing.

We all know many barns that are neglected and falling down and in most places they far outnumber those that are well-maintained.

Ironically, letting your barn fall down does not stir up the same level of passion as the third option; barns can be adapted to another use. While it may be the best use of a barn to keep it as a barn, the majority of barns will not be afforded that future. Maybe the farm has been developed into a sub-division or an office park and the barn is an anachronism in its location. Or maybe the road has been improved and widened leaving the barn right at the curb. Whatever the reason most barns will not be maintained and used as barns. So why not give them a new future?

Ironically, letting your barn fall down does not stir up the same level of passion as the third option; barns can be adapted to another use. While it may be the best use of a barn to keep it as a barn, the majority of barns will not be afforded that future. Maybe the farm has been developed into a sub-division or an office park and the barn is an anachronism in its location. Or maybe the road has been improved and widened leaving the barn right at the curb. Whatever the reason most barns will not be maintained and used as barns. So why not give them a new future?

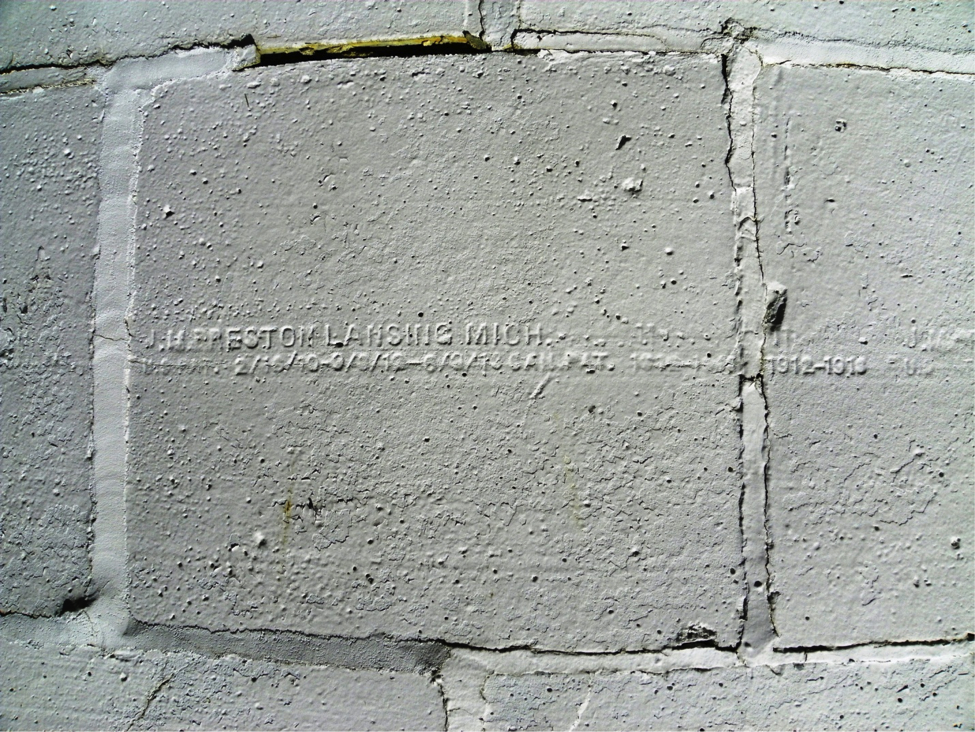

Adapting barns gets complicated fast. Unlike other 100 to 200 year old buildings, old barns suffer a different fate, which leaves them in a specifically barn-like state of disrepair. Barns were never heated like occupied buildings were; except by the residual heat of animals and manure. So their foundations have been subjected to the relentless forces of freezing and thawing each year which slowly breaks them apart. Most barns’ stone foundations succumbed to these stresses years ago. But while broken many of these barns did not fall; they just languish with gaping holes in the old stone walls.

Also on many barns the most expensive maintenance item has been left undone; replacing the roof. Holes in a roof is a barn’s death knell. Once water is tracing through a wood barn, boards and timbers alike begin to rot. In a relatively short period of time nails no longer hold boards on, mortise and tenon joints open and rot, and the building begins to sag. Just a few seasons of this kind of exposure can reduce a massive timber-framed barn to the point of no return. But like great shipwrecks, the hulk of the barn can remain for decades.

Barns are tough however because they are timberframed. Unlike ‘modern’ carpentry, timber-framing is an ancient way of framing that uses continuous wooden beams which join together post to post to post to create a singular structural network that knits floors and walls and rafters into one structural organism. In direct contrast to a house of cards, which cascades to the ground when any one card is upset, a timberframe is joined together such that if one element becomes weakened, or is compromised, other elements get loaded differently and the frame continues to do its job despite the failure.

Even the way the timbers are taken from the log contributes to the timberframe’s success; embracing the natural strength of the tree. An onion is a fairly strong spherical form until it is sliced in two and the layers begin to unravel. Wood does much the same when squared. The beams in a timberframed barn are taken from the center of the tree leaving as many rings as possible uncut. And many of the beams in a barn are not even squared at all but are still ’of the tree’; they are rounded, tapered or limb-like. This retains as much of the natural and complete strength of the tree and was less work; removing more material to make the beam square just made it weaker.

When you also factor in that the trees these barns are built of, came from slow-growing, first-growth forests you really can understand why they are still standing after hundreds of years.

What does it take to adapt a barn?

Adapting a barn has an array of considerations that must be dealt with in order to have a successful project. And while those considerations can be itemized it is important to note that opinions will vary, even between seasoned professionals, as to the best way to meet all of a project’s goals. Also for this discussion I should point out that there really is no limit as to what an adapted barn could be used for. Old barns have been used to make new houses as well as offices but there are also stores, restaurants, and convention centers all made with barn frames. Many uses can easily be accommodated in a barn.

The first consideration with respect to adapting a barn is the foundation. As mentioned before, most of the time they are damaged beyond being reasonably repaired. But even if they are not damaged a stone foundation is dramatically inferior to a new reinforced concrete foundation with provisions for both insulation and drainage, such that using the old foundation is always difficult to justify. Also, as mentioned, the barn may be in a location that does not suit its future use, so the consideration goes quickly to moving the barn. A barn frame can be moved either intact or after some kind of systematic dismantling. Selecting which tactic is best is usually a balancing act weighing how many utility wires and bridge overpasses are between the existing and new sites, against the time it would take to dismantle the barn and put it back together again. A short move with few wires may prove economical as barns are fairly light buildings and their form and materials take the stresses of the move well. However given the ubiquity of modern utilities and other improvements there are many obstacles to moving a barn great distances while whole.

When it is decided that there are too many obstacles between where the barn is and where you may want it to be (and this turns out to be the case most of the time) we have

When it is decided that there are too many obstacles between where the barn is and where you may want it to be (and this turns out to be the case most of the time) we have  the barn dismantled in somewhat the reverse order in which it was built. The roof and siding is stripped off, salvaging all of the materials possible, and then the frame is dismantled by pulling out the pegs and sliding tenons out of mortises. If done properly all of the framing materials are whole and unbroken. The barn’s parts are then loaded on trucks or into shipping containers, and then can be sent anywhere.

the barn dismantled in somewhat the reverse order in which it was built. The roof and siding is stripped off, salvaging all of the materials possible, and then the frame is dismantled by pulling out the pegs and sliding tenons out of mortises. If done properly all of the framing materials are whole and unbroken. The barn’s parts are then loaded on trucks or into shipping containers, and then can be sent anywhere.

There are additional benefits to dismantling a barn right down to its original beams and posts, particularly when it is to be adapted. When a barn is dismantled each beam can be inspected, even the joints, and if parts are found to be weak or broken, structural repairs can be made. Sometimes these kinds of flaws can go unnoticed in a barn that does not come apart and if the building is to be sent to an environment where it will be more heavily taxed, like snow or earthquake areas, it is best to know more about the condition of the frame being adapted. Taking the barn apart also affords the ability to thoroughly clean the frame. Barns are dirty environments. As shelter for farm animals and their food, a barn became the habitat for other animals such as birds, bats and opportunistic rodents. As the shelter for all of this life the cracks and crevices of a barn became filled with all kinds of unmentionables. Taking a barn apart releases decades of debris and ensures that the barn is just that much cleaner when it gets reassembled.

Lastly there is the consideration of the barn’s new use, which is a very broad topic deserving of its own separate discussion. In short though, there are a handful of important issues that must be carefully considered as they will lead directly to success or failure. The following is my list of the most important issues to be dealt with for any barn adaptation, in no particular order. I also cannot recommend how each should be solved for any given project as they each must be dealt with, basically from scratch, each time; thoroughly thought through to evaluate the impact of each decision on the project as a whole.

Structure – Barns are strong but… they are not magic. Barns were not built with respect to today’s codes and must therefore be evaluated to see how they may relate to today’s structural codes. In general we focus on the beams as the posts tend never to be overloaded; in particular the upper beams such as purlins and the rafters tend to need evaluation as do elements on the inside of the structure because the new exterior skin will contribute strength to the perimeter. Beyond this cursory mention it is not possible to predict what will need attention structurally because every barn is different in so many ways. The barn will need to be evaluated by an experienced professional team; every barn conversion does.

Insulation – An old barn is not insulated but all buildings now are required to be so, well except barns. So adapting a barn to be used as something else has to solve the issue of insulation and roof ventilation. During the last 10 years or so many new insulation products and tactics have been introduced to the marketplace making this easier to solve but with more cost and performance implications.

Circulation – Circulation is one of the most regulated events in a building. Stairs, head heights, guardrails, hallway widths etc. are always a challenge when trying to locate them within the barn without compromising the barn’s beauty. Modern stairs require more room than most barns want to allow so typically something within the barn has to move or new elements introduced. Stairs also require walls and guardrails to be safe which are alien to the barn so there are few cues as to what might be the logical or traditional solution.

Lighting – Barn’s are dark. Having never had lights and only few windows they offer no opinion as to how they can and should be opened to the sun or artificially lit. Balancing the way windows are introduced may be the most sensitive decision made with respect to a barn conversion.

Materials – One can easily find a wide range of materials introduced into a barn adaptation ranging from very modern, to very traditional, to very rustic. While I might lean one way or another in  my

my choices my best recommendation regardless of your choice is to not hide the barn. Allow as much of the barn’s frame to be seen and enjoyed.

choices my best recommendation regardless of your choice is to not hide the barn. Allow as much of the barn’s frame to be seen and enjoyed.

Making rooms – Barns are found as mostly big open spaces with lofts; maybe there’s a granary. Most new uses will want to have a bit more privacy than that and you will want to introduce walls to make separate rooms. It is always a challenge to wall off a barn without mercilessly carving it up. Once again specific recommendations are impossible without know the barn or the project’s goals but the adage ‘less is more’ tends to be applicable here. Mostly I try very hard to hide as little of the barn as possible; particularly the corners.

Regardless of whether you dismantle the barn or move it as a whole there are also a number of considerations that will require professional and experienced judgment. Among those things are the following:

1. Moving a building, any building, has a host of building code and zoning code issues (and maybe others depending on location) that need to be researched by someone qualified to do this. Talking to  your local building official may address some, or even all, of the issues but it should be noted that it is NOT the building official’s job to guide a project through the codes so if they miss something they are not responsible. It should also be noted that all of the codes / restrictions involved may not be interpreted by the same official or board; the zoning code may be administered by one official and the building code by another. Deed restrictions may be administered by yet another official or by a group and if there is a historic district there may be yet another board to appease.

your local building official may address some, or even all, of the issues but it should be noted that it is NOT the building official’s job to guide a project through the codes so if they miss something they are not responsible. It should also be noted that all of the codes / restrictions involved may not be interpreted by the same official or board; the zoning code may be administered by one official and the building code by another. Deed restrictions may be administered by yet another official or by a group and if there is a historic district there may be yet another board to appease.

2. It is not widely known but many times the ordinances and restrictions that are imposed on a given property do not agree; in those cases the most restrictive ordinance / restriction must be met. While that may seem unfair it is the way we do business so it is wise to approach the ordinances carefully and with an experienced professional. In the end the structure’s use and location has to be determined to be legal and safe.

3. If the building has been fully dismantled the building will need to meet all building codes. I have yet to meet a building official who does not agree with this. There is no ‘grandfathering’ based on the fact that it is an old building; building officials would interpret that as a self-inflicted wound if you were to argue for leniency.

4. Buildings that have been moved intact however fall into a gray area of the code, meaning that certain aspects may be able to be grandfathered however that would have to be determined carefully and clearly with the building officials. Regardless, your architect and / or builder may balk at accepting a break from some of the code requirements because they may be concerned that it could put them at risk if they design or build something that is considered less safe or prone to environmental problems.

5. There are costs on both ends of a move even if the barn is to be moved just to be a barn again and all of them should be considered before the project is begun.

a. The existing site will be left with a hole in the ground, an abandoned foundation and possibly a pile of unusable and / or rotten materials. This site will need to be cleaned up and someone will have to be responsible to perform that work.

b. The new site will need to have a foundation excavated for and built for the moved building and then the new site will need to be finish graded as required for it new use. And let’s not forget that moving a building whether intact or in parts will most likely damage some part of the building. The barn would then need to be repaired accordingly.

c. It is always a good practice to have a budget that factors all of the costs involved before the first step is taken. Many times once the first step is taken one cannot go back and must complete the project regardless of the cost.

6. Site selection and site analysis are important design exercises. The sun, wind, grading, stormwater, soil conditions, septic and well locations, are just a few of the many things that have to be factored into siting a building.

7. The planning for a building move must include analyzing the old structure to determine if it is viable, planning how the old structure will be supported, and planning for how any new elements / structures will be detailed into the old building in order to allow for its new use. One simple example, a foundation for a barn would not be the same as a foundation for a barn-house, even if it was the same exact barn, for many reasons.

Maybe it is me but I cannot ignore a building with wheels under it; even a mobile home draws me to look. But to see an old house, or an old barn, floating down a highway, or across a bridge, or through a field is like watching a loved one being delivered from a hospital; attendants paying close attention to every detail while everyone else makes way. All eyes on the patient. It is a hopeful time where thoughts are about the future and what is still possible. These buildings have so much possibility and future still in them. With the right mix of tender loving care they can enjoy a new and vibrant future for many years to come.

a field is like watching a loved one being delivered from a hospital; attendants paying close attention to every detail while everyone else makes way. All eyes on the patient. It is a hopeful time where thoughts are about the future and what is still possible. These buildings have so much possibility and future still in them. With the right mix of tender loving care they can enjoy a new and vibrant future for many years to come.